A tale of engaging students without the coursebook

Here’s a blog post going over my talk from the 5th ELT Malta Conference – originally intended for submission for conference selections, but I missed the deadline. Oops!

A tale of engaging students without the coursebook

This paper is based on a series of lessons I planned after deciding to ditch the course book, and how this engaged me as teacher and (I hope) created an engaging experience for my students. The description of this experience will be distilled into three factors I believe are key to creating moments of engaging teaching and learning: creating, sharing, and reflecting. As a disclaimer, nothing in this piece of writing is presented as things you should do; rather I invite you to compare this experience with your own and aim to encourage you to find ways of engaging yourself and your learners.

The daily life of an English language teacher

Back in 2011 I was teaching English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) in a college of further and higher education (FHE) in south east London. In this particular context there are a number of factors that may have more or less influence in how events described in the talk transpired. Some of these may be similar to things that occur in your own teaching contexts, while others may be less familiar to you.

- Availability of resources: In ESOL teaching contexts, there is not always a wealth of material available to the teacher. There certainly is not the money to be able to provide a copy of s course book for every learner. Neither are learners in a financial position where they can afford to buy these books themselves.

- Planning: Educational institutions in the U.K. are subject to periodic scrutiny by external bodies. Inspecting organisations like the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) have certain expectations with regard to planning and paperwork. This influences the internal auditing procedures that colleges and other educational institutions have in place to measure how they are performing. Where I taught, this meant writing a scheme of work (SOW) for at least six weeks of teaching in advance.

- Teaching load and sharing classes: Because of how classes are timetabled, it is common for there to be three or even four teachers that teach a particular group in a week. There will be one main course tutor, responsible for the planning of lessons and supporting the students in a particular group, and two or three other teachers who see this group maybe once or twice a week.

Finding a spark

It is in this context that I found a moment of inspiration. During a regular team meeting, my mind was not focused on the matters we were discussing – students we were going to enter for exams and their progress. Instead I was thinking about the lessons I would teach the next day; lessons I hadn’t fully prepared yet. On the SOW I was down to cover pages 126 to 129 of the coursebook being used with a particular group. Perhaps, not being wholly happy with this prospect, I was looking an opportunity to do something more interesting. I looked up and saw something on the wall, a poster for Holocaust Memorial Day; I had found my spark.

Opening space to create an experience

This all took place at 5pm at the end of my working day and I still hadn’t planned my lesson for the following morning. A quick bit of searching on the internet lead me to the Holocaust Memorial Day website and a selection of resources they had produced on the theme of ‘Untold Stories’. These included a number of images, portrait and group photos from the time of World War II; images inspired by the theme, for example, a book with empty pages; reportage photography from the Holocaust and other genocides sadly currently taking place in the world in the recent past and at present. There were also a number of resources designed for print: transcripts of eyewitness accounts of persecution; excerpts from books about or set during the war. Some of these had also been made available as audio files, and one that caught my eye was a reading from a novel, The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. I downloaded a few of the resources that interested me and headed home.

Preparing materials that would be appropriate for my morning class with a group of upper-intermediate level learners, I created a series of activities and related resources for my lesson as follows:

- A series of images designed to promote discussion, including the blank book and a map marked with places that had been affected by genocides.

- A printout and audio recording of a chapter from The Book Thief.

- An audio recording of an eyewitness account during Krist

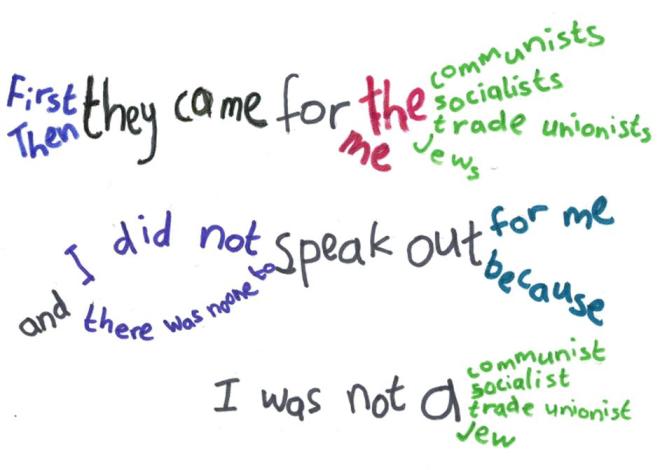

- A quote attributed to Pastor Niemoller, First they came…

What followed was quite a loosely structured discussion with the students. They began talking about the feelings that the images and audio evoked in them, and made the link with current events (at the time of the lesson there was genocide happening in Darfur, Sudan). The reading of the book excerpt was supported by the use of the reading of the text and contextualised by the audio recording of eyewitness accounts.

The ensuing discussion seemed to validate this decision to ditch the coursebook as had been originally planned. What followed was a conversation between my students and myself that flowed organically. They were clearly motivated by the topic, challenged by the resources, and keen to exchange opinions with one another. I would later go on to read that this kind of experience is one not unlike what Czikszenmihaily describes as ‘flow’ (2013: 71-72). This is a feeling when your skills are a match for the task you are undertaking, such that external worries and cares seem to disappear, and is what I witnessed in the participation of my students in this lesson.

I feel that it is far more possible to create learning opportunities with this sense of flow when you aren’t bound by the structure of a coursebook. Creating a learning experience by putting together resources like this can lead to situations where language emerges; that is, the learners are fully engaging their linguistic resources to take part in discussion and other related activities. While not adhering wholly to the materials-light precept of teaching unplugged, this does create a situation where learning can be driven by the conversation and language that the students use or want to use (Thornbury & Meddings, 2009: 8-16).

Sharing the experience

I know that I am not the only teacher to have experienced such a moment of feeling as though I and my students were in the zone and fully engaged in what we were doing. However, the question remains as to how we are able to share experiences like this. This knowledge can be of great benefit to teachers as they reflect on their practice and compare it with others, but the problem is that it can be distributed. That is, knowledge about such teaching experiences exists in pockets spread all over over the world. Pegrum tells us ‘[d]igital tools give use unprecedented opportunities to link up this distributed knowledge’ (2009: 51-52). I have certainly found this to be the case when I have managed to document my teaching on a blog.

At the time I was an avid reader of teacher blogs. In fact, this is probably where the inspiration to move away from the coursebook and create my own resources originated: I had read two blog posts written by Mark Andrews, at the time teaching at a university in Hungary, on his experience of working with his students on two series of lessons addressing the topics of bullying and Holocaust Memorial Day itself (2010, 2012).

I wrote my own blog post about my lesson and the activities that I and the students had done. What then followed was a conversation via the comment feature of a blog platform. People are able to read your post and then add a contribution of their own at the end. Quite often these can add to the ideas expressed in the initial blog post itself and even delve deeper into related topics. It was such an exchange that led to follow up lessons with my students. Comments from Mark himself and Brad Patterson, another colleague based in France, encouraged my to take the topic of the Holocaust into subsequent lessons with this particular group of students. David Warr, a teacher trainer and materials writer based in the UK, also suggested following up work on the quote from Pastor Niemoller by creating a ‘language plant’ for my students (Warr, 2014).

This exchange with colleagues from around the world – peers I was connected to online – I believe served to further my experimentation with what I was doing. I was able to incorporate different approaches in the classroom and create resources that differed from what I would normally use. It felt like I was putting something together that was more than just a single lesson; it was a series of experiences that touched my students and myself in different ways, working with multimodal resources and ecouraging us to discuss what could have been a very tricky topic to broach in an English language lesson.

Allowing everyone to reflect on the experience

Of course, all these activities so far have focused more on myself as the teacher. It is important not to forget those other key participants in any classroom: the students. All of this experimentation and sharing of ideas would have meant less if I hadn’t taken another step in my series of lessons: getting their feedback.

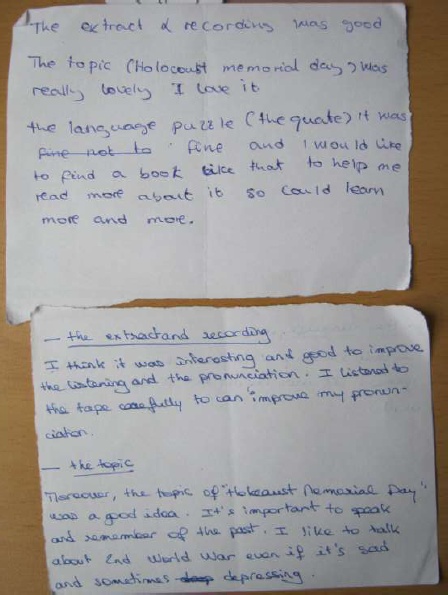

In order to allow the students the opportunity to reflect on their experience I collected feedback in the form of paper questionnaires at the end of my final lesson on the topic of the Holocaust. This was nothing too ambitious in its scope: the feedback took the form of the students being given three questions and asked to write down what they thought on slips of paper. These questions focused on the topic of the lessons, the kind of resources we used, and asked the students for their opinions on tackling historical subjects like the Holocaust in an ELT classroom.

This perhaps the most important thing that I did during this sequence of lessons and writing about them. Without direct feedback, this would have passed by in much the same way as any everyday lesson. The students would have been deprived a level of agency in what we did in the classroom; instead, by asking for their reflections and opinions it made them part of the process of planning and carrying out of the lesson and the creation of this learning opportunity.

Conclusion

As was mentioned in the introduction to this short paper, none of this is presented as what should be done in a language classroom. To present it as such would be to presume to know too much about the individual contexts in which readers of this piece will be teaching. Rather I would like to encourage readers to think about times when they did something similar to this, and how they reflected on the process.

Neither is this intended to be anti-coursebook in any way. Indeed, coursebook tasks and texts may provide stepping off points that lead to opportunities to create sequences of lessons like those described above. However, I think that by taking this element of control away from an imported set of ELT resources can allow for greater agency in the learning process for both teachers and students. If we take the opportunity to create something for our teaching, share that experience, and reflect on it properly, there will be more chance that we will engage not only the students, but everyone in the classroom.

References

- Andrews, M. 2010, Baby You’re a Firework – Classrooms on the Danube [accessed 23/12/2017]

- Andrews, M. 2012, Issues – Classrooms on the Danube accessed 23/12/2017]

- Pegrum, M. 2009, From Blogs to Bombs: The Future of Digital Technologies in Education, UWA Publishing

- Thornbury, S. & Meddings, L., 2009, Teaching Unplugged, Delta Publishing

- Warr, D. 2014, About – Language Garden [accessed 23/12/2017]